I am a research scientist in the Jensen Lab at the California Institute of Technology, where Grant is a Principal Investigator. We have worked together for about nine years, focused on structural cell biology and now, more specifically, cellular cryo-electron tomography.

Grant’s favorite way to introduce what we do is with a quote by the late, great Caltech physicist Richard Feynman:

“It is very easy to answer many of these fundamental biological questions; you just look at the thing!”

Faced with questions about how cells work, we think the best way to look is with a cryo-electron microscope. And since everything is better in 3D, we use cellular cryo-electron tomography or cryo-ET.

Understanding Cellular Cryo-Electron Tomography

Cellular cryo-electron tomography lets us look inside intact cells, without dehydration or staining, simply preserved in their native state in amorphous (“vitreous”) ice. The resolving power is high enough to let us see the shapes and arrangements of macromolecular complexes. Rather than looking at a single protein or complex, we get to see all of the cell’s machinery, frozen at a moment in time. It is a tremendously powerful technique, and, as Feynman foretold, it gives us answers to many fundamental questions about cell biology—even about the structures of the smallest unicellular organisms, bacteria and archaea.

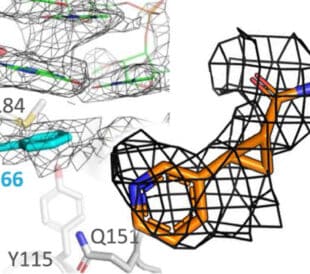

Bacteria assemble specialized type IV secretion systems (T4SSs) to inject molecular cargo into target cells. Using cryo-ET, Chang and Shaffer et al. report the first structure of a cancer-associated T4SS in vivo and describe unique membranous appendages produced when H. pylori encounters gastric epithelial cells. (Image © 2016 Oikonomou, C., Chang, YW. & Jensen, G. Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 205–220)

While our understanding of structural microbiology has been rocketing along, powered by this new technology, education has been evolving at a much slower pace. By necessity, encyclopedic textbooks of cell biology and microbiology are updated incrementally through painstaking new editions. As a result, students learn about discoveries that were made decades ago, but they don’t get to see the leaps in knowledge we’ve made in this decade. They can’t just look for themselves like they can with a light microscope in a lab course because cryo-EMs are multi-million-dollar instruments that can only be operated by highly trained specialists.

Since Grant started his lab at Caltech in 2002, scientists in our group have recorded more than 40,000 tomograms of cells. Chasing answers to various biological questions, we’ve put dozens of different species of bacteria and archaea into the microscope. The scientific results are published in articles, and in 2018, we started exploring how to share all our data openly with the scientific community by building a distributed, blockchain-based public database. Still, we think the images have even broader appeal, and bet plenty of non-specialists, from trainees in the medical field to armchair enthusiasts of biology, would love to see what bacteria and archaea really look like.

Open Access Education

In December 2020, through the Caltech Library, we launched a digital Atlas of Bacterial & Archaeal Cell Structure—a free and open-source textbook that brings cryo-ET to life, and is updated frequently to keep pace with advancements in science.

We're excited to announce the Atlas of Bacterial & Archaeal Cell Structure (https://t.co/KtZjJKUArq), an open-access multimedia textbook that shows what's inside microbial cells like never before, featuring ~150 of our best cryotomograms and animations pic.twitter.com/pXBTlyMpL5

— Jensen Lab (@theJensenLab) December 23, 2020

While the past year’s pandemic abruptly accelerated the move to digital resources, we expect the trend to continue. Even as classes move back into the physical world, textbooks don’t have to, and we think open-access digital books like this one will be a game-changer for education. Any student sitting at a computer anywhere in the world can now see what only a handful of scientists have seen in person.

Watch an on-demand Ask the Experts webinar on cellular cryo-electron tomography for an in-depth view of what bacteria and archaea really look like. Also, check out the Atlas—a passion project that we hope inspires the next generation of cell biologists and microscopists, who in turn will take the techniques further and look at things we can’t even imagine today.

//

Catherine Oikonomou is a research scientist in the Jensen Lab at the California Institute of Technology. The Atlas was launched by Oikonomou and Grant Jensen, Jensen Lab Principal Investigator, in collaboration with Caltech Library.

Leave a Reply