Flow cytometry relies on sensitive photodetectors to convert faint flashes of fluorescence from cells into measurable electrical signals. There is a need to simultaneously resolve very bright and very dim signals without forcing bright events off-scale or losing detail in the dim end to accommodate a wide range of cell sizes, expression levels, and other biological characteristics.

Choosing a detector technology is a critical step in designing an instrument that can resolve fluorescence or scatter signals from optically and morphologically diverse cells, beads, and other sample types.

Table of contents

Choosing a flow cytometry detector type

There are many important metrics to consider with selecting a detector for a flow cytometer including:

- Sensitivity / high signal-to-noise ratio: the ability to detect the dimmest fluorescence signals, down to handfuls of photons. Higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is better, as it’s critical to clearly distinguish a signal from the noise of the detector

- Low noise: noise is inherent to every detector and is the tiny, random electronic signal the detector generates in absence of incident photons, whether from thermal motion of charges on a detector surface or the random electronic signal coming from the amplification and digitization electronics

- Dynamic range: both very dim and very bright signals need to be captured

- Bandwidth/speed: event pulses are typically in the nanosecond to microsecond duration and a detector must operate fast enough to capture each pulse

- Linearity: output should stay proportional to light intensity over the usable range

- Detection efficiency: how many photons are required to generate an electronic signal that can be measured and quantified

- Gain adjustability: necessary to set a known population to an expected intensity

- Temperature independence: signal stability as ambient temperature drifts

Four detector technologies dominate fluorescence and scatter detection in modern flow cytometers:

- Photodiodes (PDs)

- Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs)

- Avalanche photodiodes (APDs)

- Silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs)

Each detector type operates on a different physical principle and comes with its own strengths and limitations.

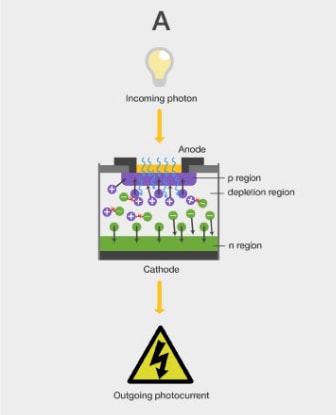

Photodiodes

Photodiodes are semiconductor devices that directly convert light into electrical current via photoconversion. They can be used without a bias voltage, with a transimpedance amplifier converting photocurrent to readable voltage. This method (“photovoltaic mode”) has the benefit of low noise, at the expense of poor linearity and speed. Add a modest reverse bias (“photoconductive mode”), and response becomes fast and linear, at the expense of increased noise. Essentially, when reverse-biased, each absorbed photon can create one electron–hole pair, with high quantum efficiency (~80%), making the photodiode a nearly unity-gain device. There is no internal gain mechanism.

Advantages

- High linearity and wide dynamic range: Configured correctly, photodiodes maintain excellent linearity across a wide range of light intensities.

- Fast response times: They can have rapid response times, making them excellent for high-speed applications.

- High signal-to-noise at higher signal levels: In conditions with sufficient light, their noise is relatively minimal. They have been successfully used as forward scatter detectors.

- Broad wavelength coverage: They are available to cover deep UV to infrared.

- Inexpensive: They are widely available and are relatively inexpensive.

Disadvantages

- No internal gain: Because they lack internal amplification, photodiodes produce very small signals under low-light conditions. In contrast to PMTs or APDs, they need external amplification and are not sensitive enough to detect fluorescence or side scatter signal in flow cytometry.

Applications

While photodiodes are not typically the primary detectors in traditional flow cytometry (where dim signals are common), they are useful in high-light situations or as ancillary detectors in optical systems requiring wide linearity. They can be used to detect forward scatter where there is an abundance of photons for a strong signal.

Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs)

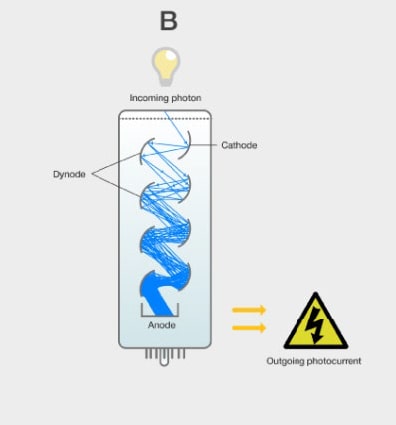

PMTs are vacuum tubes that contain a photocathode, a series of dynodes, and an anode. When a photon with sufficient energy (short enough wavelength) strikes the photocathode, it can eject a photoelectron via the photoelectric effect. A user-selectable voltage, typically hundreds of volts, is divided across the dynodes, accelerating this electron to the first dynode. On impact, the electron knocks out several secondary electrons. These are accelerated to the next dynode, releasing more electrons, and so on for each dynode. The exponentially amplified number of electrons are collected at the anode, and their signal converted to a voltage via a transimpedance amplifier. One photon makes many electrons.

The overall gain G can be approximated as:

G ≈ δⁿ

where δ is the secondary emission ratio (electrons per incident electron) and n is the number of dynode stages. A typical PMT has 10-12 dynodes. Gain can be up to ~106. Noise is extremely low, by far the lowest of all detectors described here. These are good reasons why PMTs have been the dominant flow cytometry detectors for decades.

Advantages

- High sensitivity: Very high gain and very low noise makes PMTs a good choice for dim fluorescence and scatter signal detection.

- Widely adjustable gain: Tunable gain over several decades allows signals of vastly different intensities to be placed on scale with one detector.

- Very large dynamic range: Wide dynamic range enables extremely bright and dim signals to be on scale simultaneously.

Disadvantages

- Limited spectral coverage: Response tails off in red/NIR spectral regions. NIR-optimized PMTs are available but are expensive and have poor coverage of visible spectrum region.

- Expense: PMTs cost significantly more than photodiodes, APDs, and SiPMs.

Avalanche Photodiodes (APDs)

APDs are semiconductor photodiodes operated under high reverse bias so that they exhibit internal avalanche multiplication. When a photon is absorbed, it creates an electron–hole pair which, under a strong electric field, triggers creation of new electron-hole pairs by impact ionization. These accelerate and create more electron-hole pairs, thus creating an “avalanche” effect.

Eventually, this multiplication stops in a self-quenching process. This is how APDs have internal gain, which can be tuned by adjusting the bias voltage. Each photon that strikes the detector can create its own signal, with a probability given by the quantum efficiency, at non-saturating photon flux levels.

APDs typically have higher quantum efficiency in the red/NIR range compared to PMTs but come with higher noise due to thermal dark current and avalanche noise (see disadvantages below). APD gain is adjustable by tuning the bias voltage but this must be limited to the linear response region (Fig 1).

Advantages

- High quantum efficiency in certain wavelengths: Especially in red and near-infrared, where PMTs tend to be less efficient.

- Linearity: They help provide a proportional, linear response to varying light intensities.

- Inexpensive: They are widely available and are relatively inexpensive thanks to their common use in telecommunications devices.

Disadvantages

- Noise: The stochastic nature of the avalanche process introduces an excess noise factor.

- Moderate gain: Lower than PMTs, so the signal may not be as amplified as in other detectors for very dim signals.

- Temperature sensitivity: Gain and noise are sensitive to ambient temperature variations.

Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs)

APDs have their advantages, but their maximum gain is limited by silicon physics. Would it be a bad idea to crank up an APDs bias voltage into the Geiger region (Fig 1)? Wouldn’t we get that extra signal? Yes, but with some issues.

For one, in the Geiger region once the avalanche starts it never stops. But that’s a minor impediment—engineers know how to design simple circuitry (a resistor) to quench it.

The second is more serious: while the avalanche happens, more incident photons will not produce a bigger avalanche. One, two, or fifty photons at once all produce the same detector output, resulting in a severe loss in linearity (i.e. output from the detector no longer is proportional to the incident number of photons).

However, this too has been solved in the form of the silicon photomultiplier. The silicon photomultiplier, or SiPM, is also known by several other names/abbreviations depending on the context and manufacturer:

- Multi-Pixel Photon Counter (MPCC)

- Solid-State Photomultiplier (SSPM)

- Geiger-Mode Avalanche Photodiode (G-APD or GM-APD)

The SiPM consists of a 2D array of hundreds to tens of thousands of tiny APDs, each operating in Geiger mode with its own quenching resistor. When multiple photons arrive simultaneously (within the duration of the avalanche), they will with high probability land on different microcells. The overall output is the sum of all microcells. The effective linear range is limited by the number of microcells Ncells. Roughly, the linear dynamic range in decades can be estimated:

Dynamic Range (decades) ≈ log₁₀(Ncells)

SiPMs combine the high gain (each cell produces 10⁵–10⁶ electrons per event) with the robustness of solid-state devices, offering a very large dynamic range when many microcells are used.

Advantages

- High gain: Each microcell helps provide a strong, nearly digital output.

- Good low-light resolution: They can detect light levels down to single photons.

- Extended dynamic range: By adding many microcells in parallel, the overall device can handle a broad range of light intensities.

Disadvantages

- Noise: There are high levels of detector noise, particularly as more microcells are added to the SiPM to attempt to achieve wider dynamic range

- Non-linearity: Without a sufficient number of microcells, saturation can occur with bright signals. When a large fraction of microcells fire, the response becomes non-linear.

- Limited bandwidth: There is a longer recovery period for each microcell to quench and be ready for the next incident photon to fire. This limits the speed of the device to lower frequencies than the other detectors considered here

- Fill factor is <1: There is dead space between microcells. Photons hitting dead space are not detected. The percentage occupied by microcells (“fill factor”) is typically ~50-80%.

Silicon detector comparison

To a first approximation, PDs, APDs, and SiPMs can all be thought of as the same semiconductor device (a P-N junction), just with different voltages applied across that junction, as shown in Figure 1.

There are three different voltage regimes to consider:

- No bias voltage. This results in the behavior of a photodiode.

- Reverse bias voltage below the breakdown voltage (Vbreakdown). This results in the behavior of an APD.

- Reverse bias voltage above the breakdown voltage (Vbreakdown). This results in Geiger mode, which is the behavior of each microcell in an SiPM.

Detector comparison table

| Detector | Max internal gain | Dynamic range (decades) | Noise | Typical maximum bandwidth | Peak QE*/PDE** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photodiode | 1 | ~7-8 | Very low | 350 MHz | Up to 90% |

| PMT | 105 – 107 | ~5 | Very low | >1 GHz | 20-40% |

| APD | ~102 | ~5-6 | Moderate | >1 GHz | Up to 80% in red/NIR |

| SiPM | 106 – 107 | ~6-7 | Higher | 10 MHz | Up to ~50% |

*Quantum efficiency

**Photon detection efficiency

Why does the Attune Xenith Flow Cytometer have PMTs?

The InvitrogenTM AttuneTM XenithTM Flow Cytometer uses PMTs because they have the best signal to noise (i.e. think separation index) of any detectors that we tested and that provides the best data for our customers. The high internal gain along with the wide dynamic range are important factors, providing the ability to detect both very dim and very bright signals (see the comparison table above). In combination with custom bandpass filters, this provides flexibility to enable customers to run many more panels.

Fast, flexible and spectrally brilliant analysis enabled by PMT

The Attune Xenith Flow Cytometer brings advanced spectral capabilities including UV and NIR lasers, supporting both traditional compensation and spectral unmixing analysis. It incorporates PMT detectors. Download the brochure to learn more or request a demo below.

Summary

Photodiodes, PMTs, APDs, and SiPMs each bring different advantages to flow cytometry:

- Photodiodes provide high linearity and a wide dynamic range without internal amplification. They are best suited to high-light applications or as complementary detectors

- PMTs help provide excellent sensitivity and low noise, making them excellent for detecting very weak signals. However, they have a limited linear range and have poor detection efficiency.

- APDs offer higher quantum efficiency in the red/NIR range with moderate gain and high noise characteristics.

- SiPMs combine high gain with the robustness of solid-state devices, enabling a large dynamic range by summing signals from thousands of microcells, but the noise is much larger than PMTs.

The promise of spectral flow cytometry lies in its power to extract more information from every sample—but that power is only realized when your detection system keeps pace. PMTs help deliver the sensitivity, speed, and range required to make the most of spectral experiments—whether you’re mapping immune profiles, characterizing rare cells, or building large, multiplexed panels.

For more information on optimizing your flow cytometry experiments, explore our range of advanced flow cytometry solutions.

More flow cytometry resources

- Blog: Training Your AI Image Annotation Model in Imaging Flow Cytometry

- Blog: 5 Reasons to try Spectral for Both Low and High Parameter Flow Cytometry

- Technology: Attune Xenith Flow Cytometer for spectral and conventional analysis

##

© 2025 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. All rights reserved. All trademarks are the property of Thermo Fisher Scientific and its subsidiaries unless otherwise specified.

For Research Use Only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures.

Leave a Reply