In a previous article, we presented a post on artist DeWain Valentine, whose plastic and polyester resin work can be viewed in museums and galleries across the United States. (Read Valentine’s Polyester Sculpture.) Valentine isn’t alone in finding plastic an inspiring medium. Another renowned artist, Christo, is constructing The Floating Piers, a modular dock system of 200,000 high-density polyethylene cubes, covered in yellow fabric, floating on the surface of Italy’s Lake Iseo. Visitors will be able to walk across the lake on the piers, which will be in place from June 18 to July 3, 2016.

In a previous article, we presented a post on artist DeWain Valentine, whose plastic and polyester resin work can be viewed in museums and galleries across the United States. (Read Valentine’s Polyester Sculpture.) Valentine isn’t alone in finding plastic an inspiring medium. Another renowned artist, Christo, is constructing The Floating Piers, a modular dock system of 200,000 high-density polyethylene cubes, covered in yellow fabric, floating on the surface of Italy’s Lake Iseo. Visitors will be able to walk across the lake on the piers, which will be in place from June 18 to July 3, 2016.

According to Plastics News, completing the project will require more than artistic vision. Christo and his team originally contracted with a European manufacturer of polyethylene cubes, but when the company backed out of the project due to cost concerns, Christo went into business for himself. Christo and his team have put two blow molding machines into a factory nearby and are operating them to make the cubes. The installation will be done by joining the cubes with large screws and securing them on the water by 140 anchors. When the exhibition is over, all of the materials and parts will be removed and industrially recycled, according to the project website.

So what goes into making the pier strong enough to allow people to walk on water? First, the pier will be made of high-density polyethylene, which is the strongest type of polyethylene. The material resists impacts, abrasions, moisture, stain, and odor, making it suitable for a variety of applications and industrial uses. Christo’s cubes are being constructed by a manufacturing process called blow molding, in which a measured quantity of polyethylene is “put through” and closed off on one side in the shape of a tube. Through the tube opening, the polyethylene is blown against the mold side, using compressed air. It immediately solidifies and is then – ready-made – ejected from the mold. (PlasticsEurope).

The polyethylene production process is complex. Different characteristics such as stiffness or elasticity can be imparted to the material, depending on the density of the material and its liquidity in melted form. The density and liquidity also largely depend on the amount of pressure applied during production. Producing polyethylene at low pressure forms straight, robust and tightly packed branches. The result is dense polyethylene with a firm and stiff structure. Manufacturing polyethylene at high pressure causes the particles to form a crisscross of branches and side branches, resulting in a lighter, more elastic material.

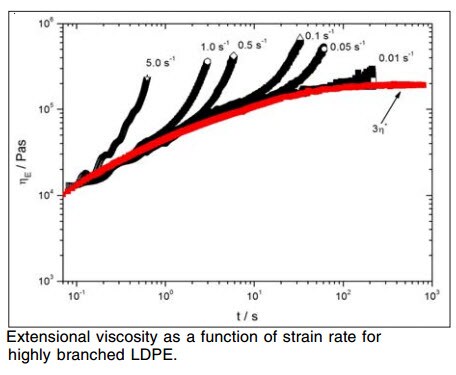

Whether polyethylene has a liquid character or not depends on its melting index, meaning how slowly or quickly the melted mass flows through a gap. Polyethylene melts are usually characterized rheologically in small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) as this mode of deformation can be obtained easily on a rotational rheometer. However, most technical processes such as blow molding are dominated by extensional deformation that interfere uni- or multiaxially with the shear flow field. Thus extensional deformation is needed together with SAOS and steady shear to obtain a complete picture of a sample’s rheological behavior.

Read the application note, Characterizing Long-chain Branching in Polyethylene with Extensional Rheology to see how the characteristics seen in extensional tests can be used to model certain processing steps such as blow-molding or film production, and for quality control applications.

And if you find yourself at Italy’s Lake Iseo at the end of June, send us some pictures of you walking across the polyethylene floating piers. We’ll post them in a future article. And that’s not an April Fool’s Day joke, either.

Leave a Reply