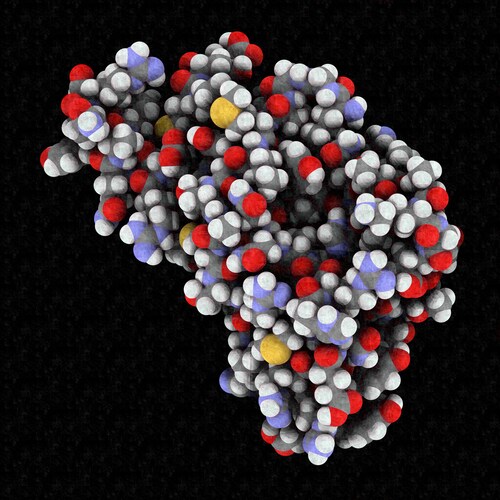

The prion protein (PrP) is implicated in a number of incurable neurodegenerative diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle, scrapie in sheep and chronic wasting disease in cervids. However, its role within cells is unknown, and therefore so is its role in disease pathophysiology. Mehrabian et al. (2016) performed an in-depth analysis of the global proteome in PrP-deficient mice, to better understand its control over other proteins.1

The prion protein (PrP) is implicated in a number of incurable neurodegenerative diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle, scrapie in sheep and chronic wasting disease in cervids. However, its role within cells is unknown, and therefore so is its role in disease pathophysiology. Mehrabian et al. (2016) performed an in-depth analysis of the global proteome in PrP-deficient mice, to better understand its control over other proteins.1

The researchers used five PrP-deficient mouse models: four cell models and one whole mouse model. They specifically chose mouse models that would cover a broad range of cellular differentiation states known to be susceptible to infection and/or that have retained the ability to (trans)differentiate. The researchers confirmed PrP deficiency in mouse models using western blot. They labeled proteins with isobaric tandem mass tags and used an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) to perform a direct comparison of the steady-state proteins.

Mehrabian et al. compared more than 1,500 proteins, finding that deficiency of a single protein could affect abundance levels of subproteomes in opposite directions in different cell types. They also found evidence that known PrP interactors were significantly enriched among proteins whose abundance levels changed the most in response to PrP deficiency. In particular, they found that PrP had a profound influence on steady-state levels of members of the myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) and brain acid soluble protein (BASP) families, which share a number of physicochemical and functional characteristics. Their study showed that PrP works with the MARCKS protein family to control neural cell adhesion molecule 1 (NCAM1) polysialylation.

This study is the first to compare the consequences of a specific protein deficiency on the global proteome, across multiple models. Similarly, Mehrabian et al. demonstrated that global proteome studies can be powerful tools, while also highlighting the effect of a single protein.

Reference

1. Mehrabian, M., et al. (2016) “Prion protein deficiency causes diverse proteome shifts in cell models that escape detection in brain tissue,” PLoS One, 11(6).

Leave a Reply