Restriction endonucleases have been a staple in molecular biology for decades, often perceived as simple tools for cutting DNA. However, these “molecular scissors” hold far more intrigue and complexity than meets the eye.

Table of contents

- What are restriction endonucleases?

- Major classes of restriction endonucleases

- Restriction endonuclease cleavage sites

- Working with Type IIS restriction endonucleases: Golden Gate cloning

- Tips for seamless Golden Gate assembly

- Application: Golden Gate cloning in plant engineering

- More resources on restriction endonucleases

- References

What are restriction endonucleases?

Restriction endonucleases, also known as restriction enzymes, are specialized proteins produced by bacteria and some archaea that cleave (usually double-stranded) DNA at specific sequences known as restriction sites.

Restriction sites are typically short, palindromic sequences ranging from four to eight base pairs in length. Methylation at these recognition sites prevents the host DNA from digesting itself, making it resistant to cleavage by its own restriction endonucleases.

DNA fragments generated by restriction enzymes can also have either sticky ends or blunt ends, depending on how the enzyme cuts the DNA strands.

- Sticky ends: These are single-stranded overhangs created when restriction enzymes make staggered cuts in the DNA. These overhangs are at the 5′ or 3′ end and can form hydrogen bonds with complementary sequences on other DNA fragments. This property makes sticky ends particularly useful in molecular cloning, as they facilitate the precise and efficient joining of DNA fragments through base pairing, followed by sealing with DNA ligase.

- Blunt ends: These occur when restriction enzymes cut straight across both DNA strands, resulting in fragments with no overhangs. Since blunt ends lack complementary overhangs, they are less efficient in ligation processes compared to sticky ends. However, they offer the advantage of being universally compatible, meaning any two blunt-ended fragments can be joined together regardless of their sequences

There are more than 4,000 known restriction enzymes today targeting 400+ recognition sequences.

For Landmarks in restriction endonucleases development, visit Basics of Restriction Endonucleases

Major classes of restriction endonucleases

Restriction endonucleases fall into four major classes or types based on their structural complexity, recognition site, cleavage site, and cofactor requirement.

| Enzyme class | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Type I | – Multi-subunit protein with both restriction and methylation activities – SAM, ATP, Mg2+ requirement – Cleavage site a variable distance from recognition site |

| Type II | – Specific recognition sequence with cleavage site within or close to recognition sequence – Generates 5′ phosphate and 3′ hydroxyl termini at cleavage site – Mg2+ requirement for most |

| Type III | – Two-part recognition sequence in inverse orientation – Cleavage site a specific distance away from one of the recognition sequences – ATP requirement |

| Type IV | – Cleavage of only methylated DNA – Cleavage site approximately 30 base pairs away from recognition site |

Type II restriction enzymes are the most commonly used in molecular biology due to their ability to cleave DNA at specific sites within or near their recognition sequences without ATP.

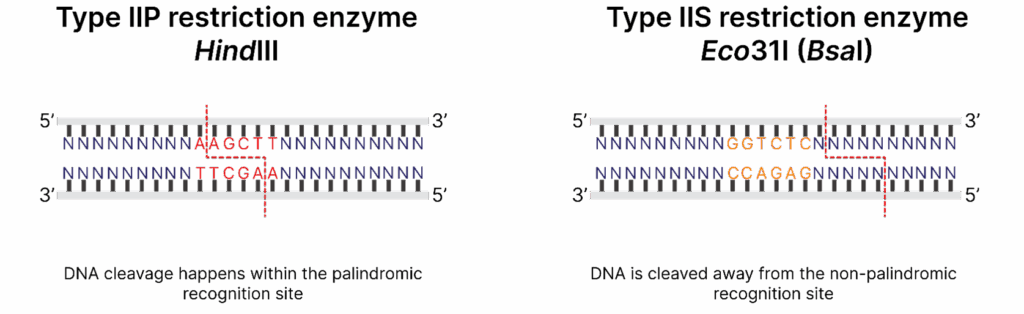

Type IIS restriction enzymes are unique in their mechanism of action. Unlike Type IIP enzymes that recognize palindromic sequences and cleave DNA within or immediately adjacent to their recognition sites, Type IIS enzymes recognize non-palindromic DNA sequences and cleave a short distance away from them. This distinctive property comes in handy in Golden Gate assembly where DNA fragments are created with custom overhangs of defined lengths and sequences that can be ligated together in a precise and seamless manner.

Restriction endonuclease cleavage sites

Isoschizomers are restriction enzymes that come from different organisms but share the restriction site and cut DNA at the same position. For example, the pair of restriction enzymes SpeI and BcuI recognizes the sequence 5′-A↓CTAGT-3′ and cleaves it in the same place, making both enzymes interchangeable.

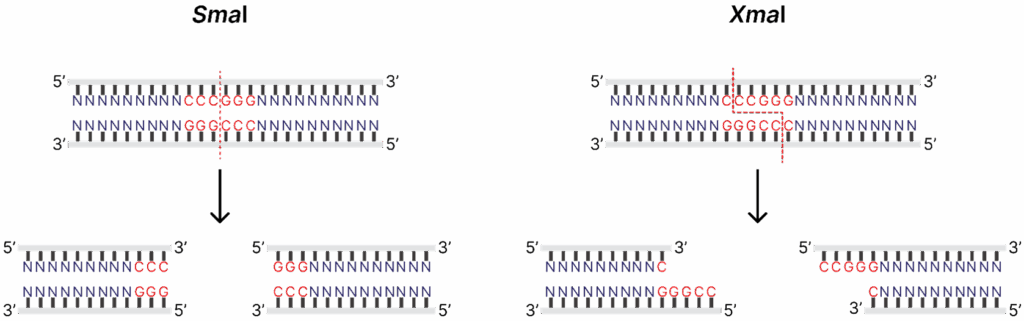

Neoschizomers are a subset of isoschizomers that recognize the same sequence but cleave DNA in a different place, thus introducing the diversity of the ends produced. Restriction enzymes SmaI and XmaI recognize the sequence 5′-CCCGGG-3′, but SmaI cuts right in the middle of the restriction site (5′-CCC↓GGG-3′), generating blunt ends, and XmaI cleaves at 5′-C↓CCGGG-3′, producing sticky ends.

Isoschizomers offer several advantages for experimental design:

- Improved performance: Newly discovered and commercialized isoschizomers are more cost-effective to produce and possess superior traits compared to classic enzymes, such as greater stability and lack of star activity.

- Methylation sensitivity: Some isoschizomers are sensitive to DNA methylation while others are not. This property is particularly useful for studying epigenetic modifications.

To learn more, visit our Digestion of Methylated DNA page

When you see an enzyme name like the aforementioned BcuI (SpeI), the enzyme listed in parentheses, SpeI, represents a prototype — the first restriction enzyme to be discovered and characterised. BcuI is a subsequently discovered isoschizomer of the prototype SpeI that recognizes and cleaves the same DNA sequence.

Working with Type IIS restriction endonucleases: Golden Gate cloning

Golden Gate assembly, also known as Golden Gate cloning, is a method that utilizes the unique properties of Type IIS restriction enzymes. The enzymes most commonly used in this technique include Eco31I (BsaI), BpiI (BbsI), and Esp3I (BsmBI).

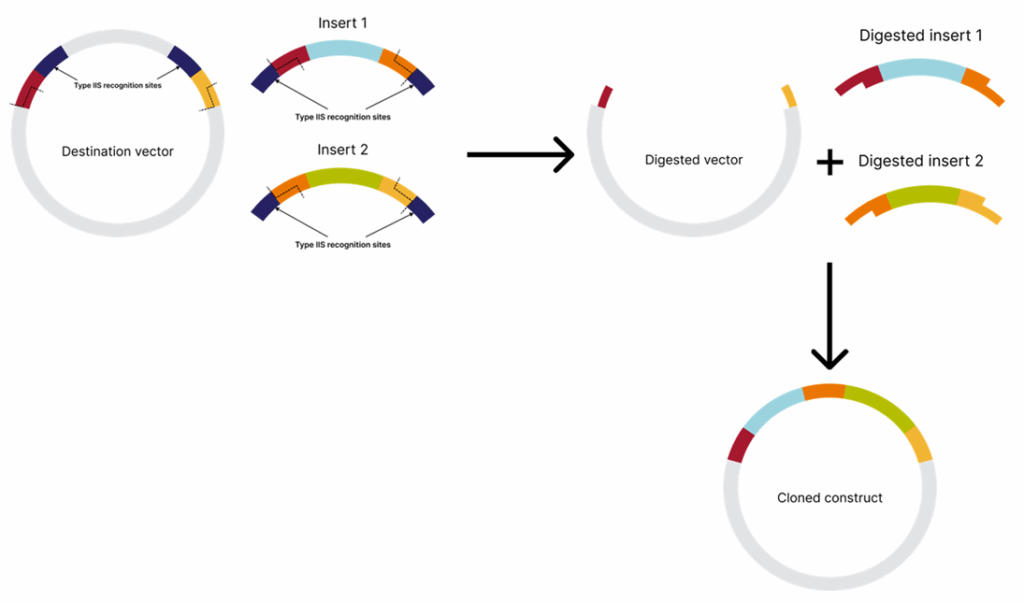

Since the recognition and the cleavage sites are separate, and DNA is cleaved at a specific distance from the recognition site and not within the sequence itself, the produced overhangs vary between cleavage sites. This enables the flexible design of constructs comprising multiple inserts.

In Golden Gate assembly, both inserts and a destination vector contain compatible cleavage sites that generate complementary overhangs, allowing the fragments to be assembled in the desired order.

The recognition sites are positioned outwards (meaning within the insert region, not the vector backbone) in the destination vector and inwards (meaning towards DNA to be assembled) in the inserts, ensuring they do not persist in the final construct. This allows simultaneous treatment of all inserts and the destination vector with the restriction enzyme and DNA ligase in a single reaction. If the inserts are not assembled into the destination vector, the recognition sites will remain, causing the restriction enzyme to linearize the vector. Since a linearized vector is inefficient in bacterial transformation, transformational background will be minimized. Golden Gate cloning allows the assembly of up to 35 DNA fragments[1].

Tips for seamless Golden Gate assembly

- Prior to conducting the experiment, use software tools like SnapGene or Benchling to visualize and confirm the orientation of the recognition sites in both your insert and the destination vector. Ensure the recognition sites face outward in the destination vector and inward in the insert. If the orientation is correct, the recognition sites will be removed from both the vector and the insert after digestion.

- Analyze the sequences of your insert and the destination vector to ensure there are no additional recognition sites that could interfere with the cloning process.

- Assemble up to 10 fragments into a single construct.

- Optimize your experimental conditions. Make sure your ligation buffer contains ATP.

Application: Golden Gate cloning in plant engineering

Owing to advancements in synthetic biology, plant research and breeding efforts have been significantly enhanced by the use of sequence-specific nucleases such as TALENs, ZFNs, and CRISPR–Cas systems[2].

Research in plant genetic engineering often involves designing complex synthetic constructs, such as new metabolic pathways, gene regulation cassettes, or constructs for genome editing[3,4]. For example, a cassette for genetic engineering typically comprises multiple inserts encoding a guide RNA (or even several guide RNAs) and a desired nuclease.

Synthetic pathway construction requires rational design of many regulatory elements to build genetic logic gates. In such cases, Golden Gate assembly is an attractive tool that simplifies the cloning process by allowing simultaneous assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction and reducing the need for extensive screening, thereby driving innovation in agriculture and biotechnology[5].

More resources on restriction endonucleases

- Invitrogen School of Molecular Biology: Restriction Enzymes Education

- Selection Tools: Conventional Restriction Enzymes Selection Tool & FastDigest Restriction Enzymes Selection Tool

- Calculator: DoubleDigest Calculator

- Catalogue: Restriction Enzymes

References

- Pryor, J. M., Potapov, V., Kucera, R. B., Bilotti, K., Cantor, E. J., & Lohman, G. J. S. (2020). Enabling one-pot Golden Gate assemblies of unprecedented complexity using data-optimized assembly design. PloS one, 15(9), e0238592. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238592

- Osakabe, Y., & Osakabe, K. (2015). Genome editing with engineered nucleases in plants. Plant & cell physiology, 56(3), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcu170

- Van Eck J. (2020). Applying gene editing to tailor precise genetic modifications in plants. The Journal of biological chemistry, 295(38), 13267–13276. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.REV120.010850

- Pan, C., Wu, X., Markel, K., Malzahn, A. A., Kundagrami, N., Sretenovic, S., Zhang, Y., Cheng, Y., Shih, P. M., & Qi, Y. (2021). CRISPR-Act3.0 for highly efficient multiplexed gene activation in plants. Nature plants, 7(7), 942–953. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-021-00953-7

- Karimi, M., & Jacobs, T. B. (2021). GoldenGateway: A DNA Assembly Method for Plant Biotechnology. Trends in plant science, 26(1), 95–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2020.10.004

- Hahn, F., Korolev, A., Sanjurjo Loures, L., & Nekrasov, V. (2020). A modular cloning toolkit for genome editing in plants. BMC plant biology, 20(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02388-2

##

© 2025 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. All rights reserved. All trademarks are the property of Thermo Fisher Scientific and its subsidiaries unless otherwise specified.

For Research Use Only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures.

Leave a Reply