I recently had the pleasure of meeting Paul Gauvreau, now a sophomore at Canyon Crest Academy in San Diego, California. His freshman year science fair project made waves locally as one of very few freshmen to make it all the way to the state competition level by enabling two different strains of kidney cells to form stable interactions where none have been able to do so previously.

We found out about this project through Mike Troutman, Senior Scientific Liaison Manager for the Genetics Division of Thermo Fisher Scientific, whom had interaction with Paul when he went to speak with the students involved in QUEST about Real Time PCR.

Paul took the initiative to speak with Mike after his presentation where they discovered a mutual love of surfing before asking him questions about his project. Months later, we heard about his success at the science fair and brought him in to find out more about the experiment.

First of all, what was the name of this project? It was called, “Artificially Formed Stable Interactions through Gene Transfection.”

And what was your goal? Knowing that stable interactions between different cells allows adhesions, communication, and functional control of each other, the objective of the experiment was to create stable interactions between two different kidney cell strains. This is significant as different kidney cell strains do not normally interact.

That was a demanding goal to set for yourself, how did you come up with the idea? In our QUEST class, we had been working on cell culture and in a recent presentation we had been discussing antibiotic resistance in organ transplants and systems. I theorized that resistance (antibiotic or rejection) was due to their inability to identify and communicate with their surrounding cells, making them “foreign cells.”

Therefore going into the experiment, you knew what the possible medical implications would be if it proved successful? To a certain extent, yes, however this is the first step in a line of experiments that still need to be conducted. The next thing I want to look at is a way to artificially create desired cells through a 3D printer.

Excellent! You’re thinking ahead. You mentioned that you asked Mike some questions while researching your project, what did he help you with? Mike was able to help me look at different ways to attack the problem. He also turned me on to online resources, like Wikipedia, for research.

Wikipedia? I thought that most high schools don’t permit the use of them as a source? Mike: I could see that; there are people who post things to the site that are not always correct and should be taken with a grain of salt. Yes, it served as more of a foundation or starting point that led to other sources to gain in-depth knowledge on the topic I was researching.

Got it, back to the experiment then; why did you use kidney cells? For two reasons, first I had heard about organ rejection issues and decided to use kidney cells because it’s one of the most commonly donated organs. And because at school I had easy access to one of the kidney cell strains, that way I would only have to find one more.

What about the plasmid you decided to use? Most every cell has some type of cadherin that is used to communicate to similar cells around it; they allow the stable interactions to be formed, permitting the passage of nutrients among other things. The brain, for example, has more than 50 types of cadherins. I found out that e-cadherin is the most common plasmid for organs. The “e” part stands for epithelial, it’s very common to tissue found throughout the body, especially on the interiors and exteriors of tissue linings. I used it based off of the types of cell strains in the experiment.

What about the plasmid you decided to use? Most every cell has some type of cadherin that is used to communicate to similar cells around it; they allow the stable interactions to be formed, permitting the passage of nutrients among other things. The brain, for example, has more than 50 types of cadherins. I found out that e-cadherin is the most common plasmid for organs. The “e” part stands for epithelial, it’s very common to tissue found throughout the body, especially on the interiors and exteriors of tissue linings. I used it based off of the types of cell strains in the experiment.

Mike: How is it different from other interaction based proteins? Most interaction based proteins are very specific, like keys to a lock. However, I used this to my advantage. By using the same e-cadherin in all the cells, it served as a “universal key” to get the cells to communicate and interact with each other.

That seems like a difficult thing to accomplish. So, considering all that you went through before and during the experiment, what was the hardest part? Getting the materials! Some of the stuff I used was really expensive. The cell strains were the hardest. A lab at UCSD donated them.

Wow, how did you accomplish that? My teacher’s dad has a lab at UCSD and his neighboring lab was working with bunch of kidney cells. I talked to them about my experiment, so they gave me the kidney cells I needed.

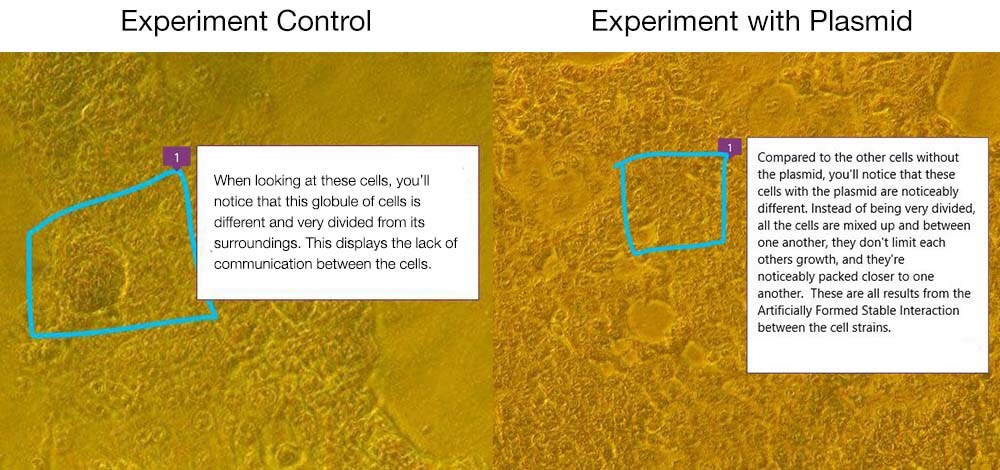

Ok then, what was the most exciting part of the experience? The whole thing actually. I had spent weeks doing transfections, controls, and many different stages and steps letting it grow out over the weekend. When I came in one Monday, I looked at the control first, and they looked just the way I expected. But when I looked at the experimental samples under the microscope, you could clearly see the difference between the two. It baffled me, because it was so easy to see!

If you had to do it all over again, would you change anything? I did have to do it over again because I accidentally stored the cells in the wrong medium and they all died. But I was able to replicate the experiment, store them correctly and take pictures for the science fair. Other than that, no, I don’t think I would change anything.

Do you know what you’re going to work on for this year’s science project? It would be the next step from here, how to artificially form tissues using a CAD based program like solid works and a 3D printer.

Do you have what you need to get started on that? Not at the moment. I will need funding in order to work on the 3D printer.

Funding is a problem that plagues most all scientists, wouldn’t you agree? That’s all for Part 1, come back soon to find out what happened at the State Science Fair!

If you have any questions that you want Paul to answer, feel free to leave a comment and we’ll see if he can answer them before the next blog post.

Thanks!

QUEST program at Canyon Crest Academy: http://cc.sduhsd.net/Programs/Quest/Research/Program-Summary/index.html

For more on Paul’s project: https://www.usc.edu/CSSF/Current/Projects/S0511.pdf

Products Used in experiment:

Gibco™ Cell Culture Media

Gibco™ Fetal Bovine Serum

Invitrogen™ Lipofectamine Reagents

Invitrogen™ Plasmid Mini Prep

Gibco™ Cell Culture Reagents

All products are for Research Use Only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures.

Leave a Reply