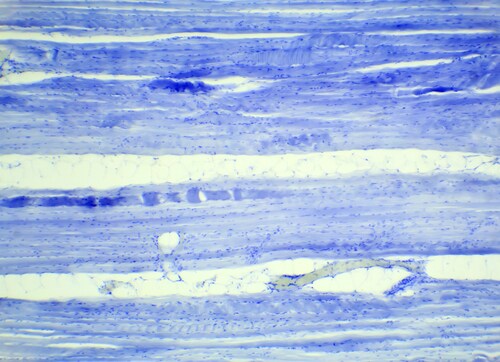

Skeletal or voluntary muscle tissue comprises fiber bundles made up of multi-nucleated single cells that fuse together following myoblast differentiation (reviewed here). Murgia et al. (2015) developed a mass spectrometry–based proteomics workflow that is capable of characterizing the proteome in single muscle fibers.1 Using specific markers within the different muscle types, they determined that analysis of the proteome is sufficient to assign its type and furthermore can show quantitative and qualitative differences in mitochondrial function.

Skeletal or voluntary muscle tissue comprises fiber bundles made up of multi-nucleated single cells that fuse together following myoblast differentiation (reviewed here). Murgia et al. (2015) developed a mass spectrometry–based proteomics workflow that is capable of characterizing the proteome in single muscle fibers.1 Using specific markers within the different muscle types, they determined that analysis of the proteome is sufficient to assign its type and furthermore can show quantitative and qualitative differences in mitochondrial function.

Anatomists classify skeletal muscle fibers as either slow (type I) or fast (2A, 2X and 2B), according to the velocity of contractility and myosin heavy chain (Myh) isoforms. A further division describes type I fibers as slow oxidative, 2A and 2X fibers as fast oxidative glycolytic, and 2B as fast glycolytic, according to metabolic profiles. There are therefore metabolic as well as structural differences between the muscle fiber types. Disease can affect all muscle tissue, although some conditions are specific to muscle fiber type. Remodeling at the fiber level also occurs in response to diet, hormone changes, metabolism and change in exercise.

Although researchers can study single muscle fibers, examining them proteomically is difficult, since high-abundance sarcomeric proteins such as myosin often mask less prevalent proteins, making it difficult to characterize subtle changes due to remodeling or disease.

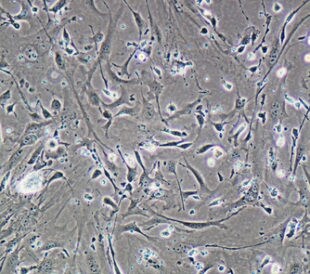

Murgia et al. took soleus and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle from freshly killed wt CD1 mice as representative of all four major fiber types. Following mechanical dissociation, they lysed the fibers, then digested them for proteomic analysis, using an in-stage tip method workflow in a single vessel to minimize sample loss. They used an Easy-nLC 1000 ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system in combination with a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (both Thermo Scientific) for proteome characterization. Using MaxQuant for data analysis, the researchers searched the Uniprot FASTA mouse database with the Andromeda search engine for protein identification.

The team also analyzed whole muscle samples to obtain a deep analysis of the skeletal muscle proteome, using FASP (filter-aided sample preparation) followed by isoelectric focusing to separate the peptides prior to mass spectrometry–based proteomic analysis. They used these results alongside those from the single muscle fiber analysis, employing the “match between runs” feature of MaxQuant.

Murgia et al. combined the two data sets, using the deep skeletal muscle proteome results to match for the single fiber peptide analysis. From this, they obtained 7,174 protein identifications, with 50% of these corresponding to Myh and other sarcomeric proteins. Furthermore, on analysis of Myh isoforms, the team found that the results correctly identified the type of fiber under investigation. To confirm this finding, they verified intra-assay variation using half of each fiber for different runs. In addition, they also compared results using a PrESTs (protein epitopes signature tags) approach and by comparison with traditional electrophoresis for Myh isoforms.

Once these results were validated, the researchers found they could show clustering of function-specific proteins within muscle fiber types. Analysis of proteomic data also showed 654 proteins annotated specifically as mitochondrial, with approximately 270 identified per individual fiber. The scientists also found differences in metabolic pathways existing between fiber types.

In conclusion, Murgia et al. suggest that the workflow is capable of analyzing quantitative and qualitative differences in muscle fiber function at the mitochondrial level. Since skeletal muscle disease frequently affects these cell organelles, the methodology presented could be valuable for studying pathological conditions in addition to response to exercise and drug treatment.

Reference

1. Murgia, M., et al. (2015) “Single muscle fiber proteomics reveals unexpected mitochondrial specialization,” EMBO Reports 16 (pp. 387–95), doi: 10.15252/embr.201439757

Leave a Reply