The protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi causes both acute and chronic Chagas disease. Although the available pharmaceuticals are effective during the early stages of infection, they are highly toxic and produce adverse effects in a significant percentage of patients (40%). Additionally, even prompt treatment may not prevent acute Chagas from progressing into the chronic form. The World Health Organization estimates there are 7–8 million infected individuals in Latin America, where the disease is endemic.

The protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi causes both acute and chronic Chagas disease. Although the available pharmaceuticals are effective during the early stages of infection, they are highly toxic and produce adverse effects in a significant percentage of patients (40%). Additionally, even prompt treatment may not prevent acute Chagas from progressing into the chronic form. The World Health Organization estimates there are 7–8 million infected individuals in Latin America, where the disease is endemic.

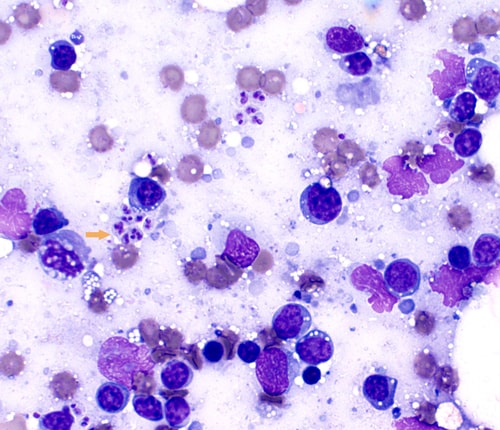

Because the vast majority (70%) of approved pharmaceuticals target plasma membrane proteins, characterization of the T. cruzi subproteome is an essential step in drug development. In this study, Queiroz et al. (2014) used complementary techniques they previously identified for this purpose: (1) cell surface protein biotinylation followed by streptavidin affinity chromatography and (2) cell surface trypsinization (Shave) of intact proteins.1 It is important to note that T. cruzi exhibits several forms at different stages of the lifecycle, including trypomastigote (the form at the time of initial human infection) and amastigote (the form once the parasite enters a human cell). In this work, the team collected trypomastigotes from infected HeLa cell cultures and incubated these to generate axenic amastigotes; they used both forms in this study.

The researchers enriched the samples using the two strategies described prior to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis (LC-MS) on an LTQ Orbitrap Velos hybrid ion trap–Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). For data management, they relied upon Xcalibur software (revision 2.1) and Proteome Discoverer software (revision 1.3) for searching against existing databases, along with ProteinCenter software for protein-level interpretation (all Thermo Scientific). The protein group identifications yielded per enrichment type for trypomastigotes and amastigotes, respectively, were as follows: biotinylation, 576 and 693; Shave, 1049 and 1118; and control (Shave minus trypsin), 679 and 626. The majority of these were predicted transmembrane proteins, while a much smaller percentage were predicted GPI-anchor and/or ER/Golgi signal proteins. Interestingly, the control samples produced similar findings, confirming the suspicion that both life stages likely release membrane vesicles containing virulence factors. Trypomastigotes and amastigotes shared 61% of the protein group identifications.

The team collapsed the protein group identifications drawn from both enrichment techniques into a single data set labeled “surface/exposed proteins,” for the purpose of seeking plasma membrane subproteome-associated drug targets. Ideally, these targets would be unique to the parasite and located on the cell surface or excreted/secreted by the cell. With this in mind, the researchers highlighted 251 and 245 “hypothetical” surface proteins from the database for trypomastigotes and amastigotes, respectively. Of these, 72 and 66, respectively, occurred in only one life stage, and 92 and 101, respectively, contained a minimum of one predicted transmembrane domain.

Queiroz et al. painted a broad picture of the likely relationships between identified proteins and the roles these play in parasite–host interactions. The surface/exposed proteins contained representatives from six enzyme activity groups: transferases, oxidoreductases, hydrolases, lyases, isomerases and ligases. For the most abundant enzymes, transferases, the notable representatives included Ser/Thr protein kinases, adenylate kinases and Tyr-protein kinases. The team also highlighted several stage-specific enzymes. For amastigotes, these were largely involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism; for trypomastigotes, these were mostly associated with glycolysis and phospholipid biosynthesis.

Specific to trypomastigotes, the researchers noted superoxide dismutase as an enzyme previously identified as a potential drug target. Because proteases make excellent therapeutic targets, the team highlighted those as well. For amastigotes, the predominant representatives were threonine endopeptidases; for trypomastigotes, they were ubiquitin tiolesterases and proton-transporting ATPases. For the surface/exposed proteins in both life stages, the most abundant enzyme class was that of exo-α-sialidases, followed by ATPases.

Finally, the team discussed glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, which coat the parasite plasma membrane and mediate several interactions between the parasite and host. In this study, they identified 37 protein groups likely to be GPI-anchored in the subproteomes of both life stages. They observed most of these in both sample types, with only 9 specific to amastigotes and 2 specific to trypomastigotes.

Queiroz et al. offer this study as a comprehensive profiling of the cell surface subproteome of T. cruzi by both biotinylation with streptavidin affinity chromatography and Shave enrichment techniques using Orbitrap-based MS. Their work reveals and confirms a broad arsenal of proteins mediating the parasite–host relationship, highlighting stage-specific enzyme classes that may be potent targets for novel drug therapies to combat this ubiquitous infectious disease.

Reference

1. Queiroz, R.M.L., et al. (2014) “Cell Surface Proteome Analysis of Human-Hosted Trypanosoma cruzi Life Stages,” Journal of Proteome Research, dx.doi.org/10.1021/pr401120y [e-pub ahead of print].

Post Author: Melissa J. Mayer. Melissa is a freelance writer who specializes in science journalism. She possesses passion for and experience in the fields of proteomics, cellular/molecular biology, microbiology, biochemistry, and immunology. Melissa is also bilingual (Spanish) and holds a teaching certificate with a biology endorsement.

Leave a Reply