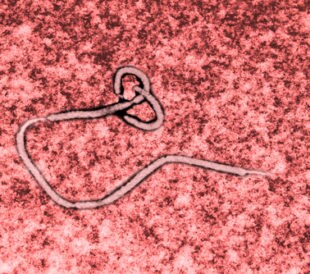

Clinton et al. (2014) recently published a paper outlining the use of mimics as an elegant solution to researcher safety while working with a deadly pathogen.1 Ebola virus (EBOV) infection causes a devastating hemorrhagic disease in humans, with almost 60% fatality in most outbreaks where medical care is limited. In order to research novel therapeutics and investigate potential virus weaknesses, laboratories must either cope with the stringent biosafety requirements necessary for this biohazard or find a non-hazardous, non-lethal model to work with.

Clinton et al. (2014) recently published a paper outlining the use of mimics as an elegant solution to researcher safety while working with a deadly pathogen.1 Ebola virus (EBOV) infection causes a devastating hemorrhagic disease in humans, with almost 60% fatality in most outbreaks where medical care is limited. In order to research novel therapeutics and investigate potential virus weaknesses, laboratories must either cope with the stringent biosafety requirements necessary for this biohazard or find a non-hazardous, non-lethal model to work with.

Clinton et al. have identified a viral protein region that is 90% conserved across all EBOV species. Using this information, they created two mimics that are suitable as drug-screening targets. From previous research in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, the team chose to focus on the N-trimer region, since it is involved in viral entry into cells. This area has shown success in drug targeting against HIV infection, which enters cells using a similar mechanism.2 During EBOV infection, the N-trimer region interacts with its native ligand, a C-peptide region in the GP2 viral protein, altering conformation to expose a vital binding site that allows viral entry into host cell endosomes.

Once created, the researchers characterized their novel mimic products using a variety of methods to examine conformation, structural binding motifs and interactions. They conducted all reactions and analyses at a pH of 5.8 to simulate the endosomal conditions within the endosome during virus trafficking.

Using X-ray crystallography, the team found that the N-trimer mimics adopted a typical trimeric coiled structural conformation as seen in native EBOV. They confirmed binding potential with C-peptide and established specificity using mutated forms of the mimics. Furthermore, using surface plasmon resonance to examine interactions, Clinton et al. could demonstrate similar binding affinity for C-peptide as found in their work with HIV.3

The team found the crystal structure of the mimics was similar to the native EBOV protein region, and further examined protein interactions with the C-peptide region using the MONSTER protein interaction server for analysis. The results from this gave further insight into potential sites for therapeutic inhibition.

With phage display screening, the researchers analyzed binding interactions with the mimics. In both solution and solid phases, the team found that the ligands bound tightly to the mutants, but showed no activity when presented with mutated forms. They further tested binding interaction using mirror-image mimics to evaluate these isoforms as potential therapeutic targets. Since these forms do not occur naturally, they are resistant to proteases and may have a longer half-life in vivo. Furthermore, they are also capable of blocking targets larger than the ones blocked by smaller therapeutic molecules, and show success in inhibiting HIV cell entry.3

Using one of the N-trimer mimics, Clinton et al. successfully blocked viral entry in an EBOV pseudovirus system expressing GP2 protein on the cell surface of HIV. However, the effect was less marked when used against wild-type EBOV under BSL4 conditions. The research team notes that in order for successful inhibition, therapeutic agents interacting at this level need to enter the cell endosome for activity. Neither of the two N-trimer mimics expresses endosomal recognition tags.

Clinton et al. conclude that the two mimics that the team designed and characterized should be useful drug discovery targets in EBOV research. Furthermore, they note that since the prehairpin N-trimeric region is well conserved across all filoviruses, further examination could uncover therapeutic options for Marburg virus that could be useful as broad-spectrum therapeutics.

References

1. Clinton, T.R., et al. (2015) “Design and characterization of ebolavirus GP prehairpin intermediate mimics as drug targets,” Protein Science 24(4) (pp. 446-63), doi: 10.1002/pro.2578.

2. Francis, J.N., et al. (2012) “Design of a modular tetrameric scaffold for the synthesis of membrane-localized D-peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 entry,” Bioconjugate Chemistry 23(6) (pp.1252–58), doi: 10.1021/bc300076f.

3. Welch, B.D., et al. (2007) “Potent D-peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 entry,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 104(43) (pp.16828–16833), doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708109104.

Leave a Reply